Identified as a critical need for youth organizations to deliver programs on reconciliation (TRC call to action #66) and in The Grove’s first year report (Homewood Research Institute) for culturally appropriate programming, this project will investigate what Indigenous Reconciliation programming looks like in mental health service settings and beyond.

Supporting The Grove Hub’s Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Indigenous Reconciliation Implementation Plan, this project will first conduct a scan of academic and community-focused literature on Indigenous Reconciliation through a youth-led working group.

Scheduled to meet every two weeks, over Summer 2022, (following The Grove’s current and previous working group schedules), we will come together over eight online meetings (could be in-person/ hybrid).

Tuesday 7th June

Tuesday 7th JuneWhat a great first session! I was nervous to begin with but I had no reason to be. I have been working with this group of young adults for just over a year on different projects through my partner organization. However, its always nerve wracking when you start using a new practice! But Pre-Texts IS different, I am not at the centre, I am not the one making the decisions. In this context it is a shared collaborative space.

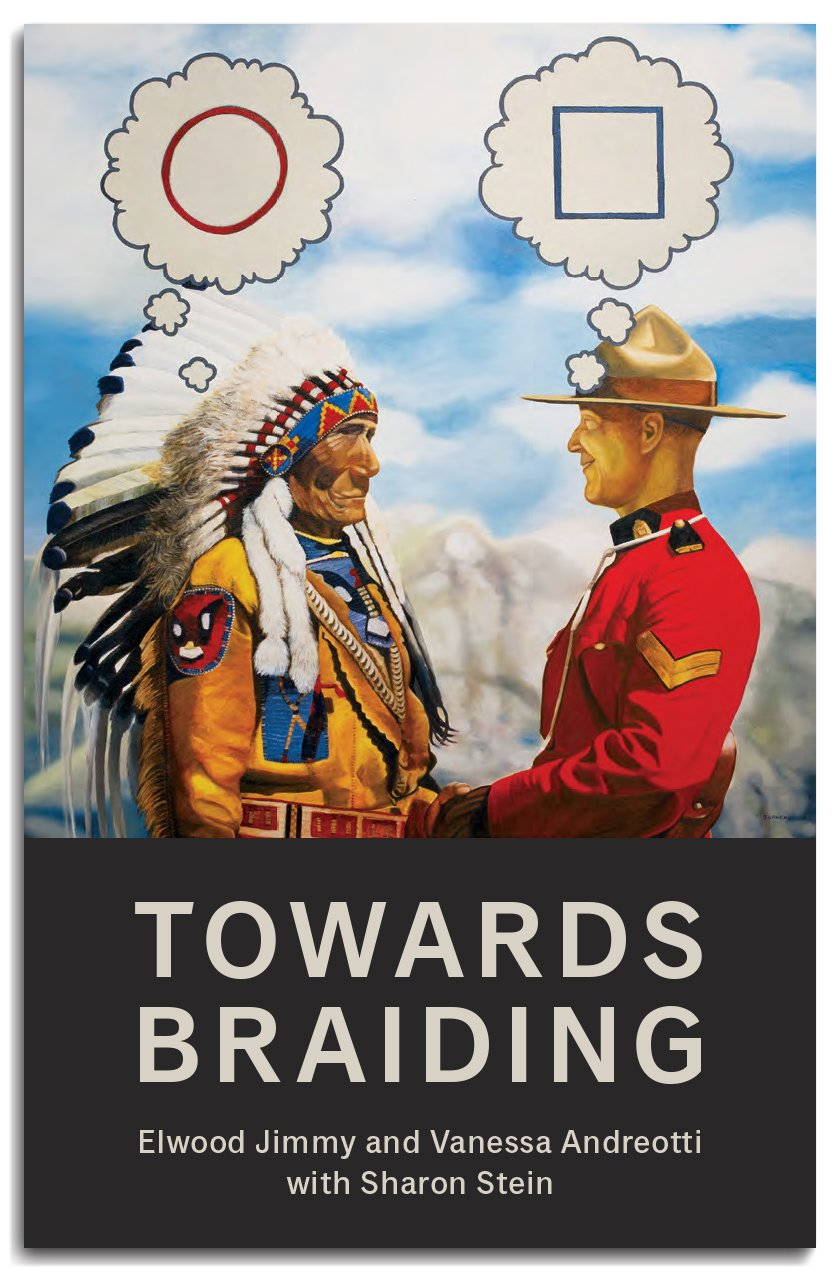

Today we worked on our main text (pictured here). A text that has been written and supported by community artists, researchers, Indigenous and non-indigenous community members here in Guelph. Towards Braiding discusses complexities in decolonizing organizations that employ or who seek Indigenous people to conduct their ‘Indigenization’ or ‘decolonization’ work.

I started by reading the Preface to the book to the working group while they doodled their responses. Next we moved to asking the text questions – which revealed some important and key questions that the partner organization and their staff need to be asking moving forward in their process of Truth and Reconciliation. We then chose questions to speculate on and respond to. Ensuring that there were no right or wrong answers here was key. Once completed I invited the group to verbally share on a question they had responded to. What was revealing here again was the impact of the group participating in the Indigenous Reconciliation Plan working group and the literature they had read for this group had clearly had an impact on them.

To close out the session we ended with asking the question “what did we do?” The group were enthusiastic to share their drawings but also commented that this way of working allowed for them to engage with the text in a completely new way. One remarked “This activity made me realize that we can start this work [of reconciliation] without our hand being held by those in higher positions or adults in power.”

Set for two weeks time the group will pre-read the chapter “When things fall apart…” and choose to go on a tangent with either our main text or the texts that we chose to include in our inquiry (below). Looking forward to seeing what our next meeting brings!!

National Indigenous Peoples Day

Today was National Indigenous Peoples Day in Canada, which is a day of celebration of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis cultures. This is also an opportunity for people to educate themselves about the Indigenous communities living in their local area.

Our session opened with a check-in about what the day represented for each of us and how these sessions were widening our perspectives on the history of colonialism in Canada. Being in this space with each other feels very unique as we are all learning at the same time therefore the power dynamic shifts.

What’s A Tangent?

Moving into the tangent exercise seems to be difficult. It does not flow as well as it did in the training. I am wondering if I am not explaining the exercise correctly. In the moment tangents are looked for. Perhaps this is just the way that these sessions need to be for the group.

However, lots of interesting questions came from reading through the tangents and asking questions.

What do you do when you don’t understand an Indigenous perspective from your own point of view?

Although this session only focused on the tangents, there was much that came out of doing this exercise. We are trying to challenge one’s intentions, acknowledge the colonial language we have been conditioned to using and accepting that there is no formula for the work of reconciliation to be done.

5th July 2022

Creating Art

This week we were given the opportunity to create a piece for an online Improv festival which is ideal as we are working on creating Blackout Poetry.

Again, we started with a check-in. The gaps between sessions are difficult to gather momentum in the process of inquiry. However, the commitment to exploring what reconciliation means in the contexts we find ourselves in does not fade.

The tangents take us to thinking about intentions vs cultural appropriation and asking what happens when we see the good intention but it does not match the Indigenous intention setting? We note that focusing on Indigenous propriety is important. We ask, how are The Grove Hubs involved in the healing process with Indigenous peoples? How do you depict and talk about trauma without re-traumatizing and stereotyping? We don’t know the answers to these questions and we know that there is not a one size fits all approach.

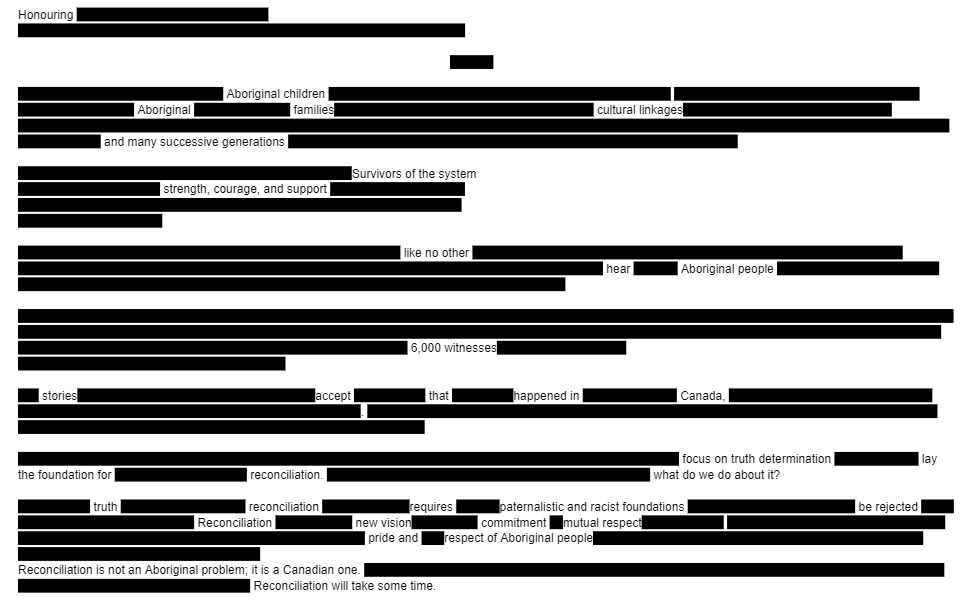

Blackout Poetry

The text we used to create our poetry came from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report preface. This opened up many ideas for how and what we focus on as a place of importance.

Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future

Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Preface

Canada’s residential school system for Aboriginal children was an education system in name only for much of its existence. These residential schools were created for the purpose of separating Aboriginal children from their families, in order to minimize and weaken family ties and cultural linkages, and to indoctrinate children into a new culture—the culture of the legally dominant Euro-Christian Canadian society, led by Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald. The schools were in existence for well over 100 years, and many successive generations of children from the same communities and families endured the experience of them.

That experience was hidden for most of Canada’s history, until Survivors of the system

were finally able to find the strength, courage, and support to bring their experiences

to light in several thousand court cases that ultimately led to the largest class-action

lawsuit in Canada’s history.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was a commission like no other in Canada. Constituted and created by the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which settled the class actions, the Commission spent six years travelling to all parts of Canada to hear from the Aboriginal people who had been taken from their families as children, forcibly if necessary, and placed for much of their childhoods in residential schools.

This volume is a summary of the discussion and findings contained in the Commission’s final multi-volume report. The Final Report discusses what the Commission did and how it went about its work, as well as what it heard, read, and concluded about the schools and afterwards, based on all the evidence available to it. This summary must be read in conjunction with the Final Report. The Commission heard from more than 6,000 witnesses, most of whom survived

the experience of living in the schools as students.

The stories of that experience are sometimes difficult to accept as something that could have happened in a country such as Canada, which has long prided itself on being a bastion of democracy, peace, and kindness throughout the world. Children were abused, physically and sexually, and they died in the schools in numbers that would not have been tolerated in any school system anywhere in the country, or in the world.

But, shaming and pointing out wrongdoing were not the purpose of the Commission’s mandate. Ultimately, the Commission’s focus on truth determination was intended to lay the foundation for the important question of reconciliation. Now that we know about residential schools and their legacy, what do we do about it?

Getting to the truth was hard, but getting to reconciliation will be harder. It requires that the paternalistic and racist foundations of the residential school system be rejected as the basis for an ongoing relationship. Reconciliation requires that a new vision, based on a commitment to mutual respect, be developed. It also requires an understanding that the most harmful impacts of residential schools have been the loss of pride and self-respect of Aboriginal people, and the lack of respect that non-Aboriginal people have been raised to have for their Aboriginal neighbours.

Reconciliation is not an Aboriginal problem; it is a Canadian one. Virtually all aspects of Canadian society may need to be reconsidered. is summary is intended to be the initial reference point in that important discussion. Reconciliation will take some time.